Herbal “Worts”

by Valle Novak

Many gardeners will recognize today’s little play on words. Indeed, back in medieval times the term “worts” was used for many plants – generally the useful ones, which we now term “herbs.” Later, wort would be used for more common plants, but for several centuries, “lungwort,” “woundwort,” “liverwort” and many dozens of others were the common name given to a variety of healing (and some not so healing) herbs.

Most often, the name came from the Doctrine of Signatures, which held that a plant’s form, coloration, shape, etc., made clear its use: therefore “lungwort” (Pulmonaria), with its spotted leaves resembling lungs, was a cure for all kinds of lung problems and “woundwort” (Stachys palustris) not only staunched bleeding wounds but was thought to also ease bleeding ulcers.

Many of the beliefs and superstitions regarding these plants proved to be of actual value, and many others have gone the way of the Dodo, to be nearly forgotten. I think this is a shame, since the history of plants makes them more meaningful; so today, with the help of Nicholas Culpeper, M.D., who combined his astrological studies with the study of plants during his short life (he was only 38 when he died) and published his Family Herbal in 1649, we’ll explore some of the ‘worts’ of his time, and see just how many we have growing in our own gardens.

Though John Gerard’s and John Parkinson’s herbals had been previously published (in 1597 and 1640 respectively) Culpeper felt that the fact they were based on Latin and used many imported herbs made them neither comprehensive or available to the poor people of the time. To emphasize the need to communicate with his humble clients, he translated the entire London Pharmacopoea from Latin into English, and used only locally available herbs, even telling some of his patients where to find and gather their own.

With that little history as background, let’s track down our own gardens’ warts – er, worts!

Bloodwort, or Common Dock (Rumex obtusifolius) was, and is a common weed which includes burdock and sorrel in its family. It was thought to “cleanseth the blood and strengthen(s) the liver” and even today the Yellow Dock or Curled Dock is used in modern practice as a blood purifier, a gentle laxative and a tonic (since it is an iron-carrier).

Brimstone-wort, Fennel (Foeniculum Officinale), was also called Sulphur-wort and earlier recommended by ancient herbalists Galen and Dioscorides for helping those “troubled with lethargy, frenzy, giddiness of the head, the falling-sickness, long and inveterate headache, palsy, sciatica and the cramp.” The juice was used, mixed with vinegar and rosewater, and “put to the nose.”

Bruisewort, Little Daisy (Bellis perennis) – is the short little pink or white daisy that grows in lawns (we often called them English daisies). The crushed fresh leaves still soothe wounds and help healing of deep bruises just as in Culpeper’s day. The Ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) used in the same manner, was also esteemed to “disperseth and dissolveth the knots or kernels that grow in the flesh … or bruises due to falls and blows.”

Coughwort, Colt’s foot (Tussilago farfara) is a dandelion look-alike but with broader, shinier (and to me, more palatable) leaves. Used distilled for coughs in Culpeper’s day, it is still an important ingredient in many over-the-counter cough mixtures.

Colewort, Avens (Geum urbanum) is a common wayside plant used in the 17th Century to strengthen the stomach, stitches in the side, and comfort ruptures. It is still widely used today as an antiseptic, aromatic, astringent, stomach tonic and for debilitating diseases, especially of the intestinal tract, such as colitis.

Goutwort, Goutweed, (Aegopodium podagraria) is also known as Goat’s foot since its leaves resemble them. It was used to heal gout and sciatica, and today is still used as a diuretic and sedative for arthritic and rheumatic pains.

Have you noticed anything so far? Those old-timers weren’t so far off the track, were they? Maybe, since they had to use their own wits and imagination, their trial-and-error, their belief and hope in a beneficent Creator and loving Mother Earth provided them with many of the right answers. Let’s continue.

Kidneywort, (Umbilicus ruprestris), was used distilled for “a hot stomach, a hot liver, or the bowels,” and as a poultice or rub to heal pimples and “other outward heats.” Though not in use today, it is still considered a cooling diuretic, and a good poultice for hemorrhoids. It was used in the 19th century as a remedy for epilepsy.

Motherwort, (Leonurus cardiaca), was described by Culpeper as follows: “It makes mothers joyful and settles the womb; it is of use for trembling of the heart, and fainting and swooning. There is no better herb to take melancholy vapours from the heart and to strengthen it.” He recommended keeping it in syrup or as a conserve. Today, it’s a heart tonic for angina pectoris, helps to lower blood pressure, and regulates a woman’s return to normal after childbirth and well as easing painful periods.

Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) was also used in female disorders, as well as (when mixed with hog grease) taking away wens, knots and kernels under the skin. It is still used for women’s problems and as a nervine for convulsions.

Sneezewort, (Achillea ptarmica): “The powder of the herb snuffed up the nose, causes sneezing and cleanses the head of tough slimy humours.” Closely related to yarrow, it does not really resemble it. Once a famous herbal medicine, also used to ease toothache, it was officially discarded by the medical profession 200 years ago.

Remember, we said that some worts were useful as well as healing. A couple of years ago at a class at the Clark Fork Field Campus, I saw our next one in action.

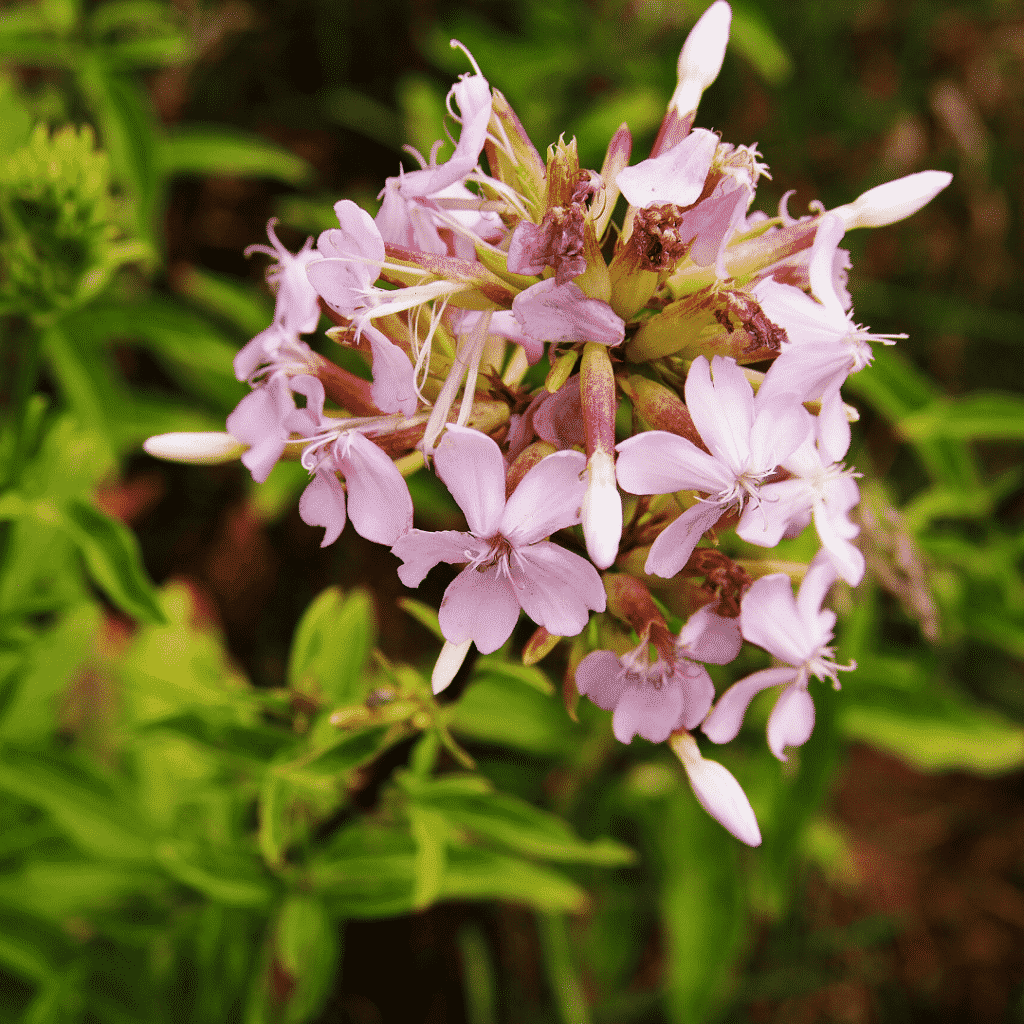

Soapwort (Saponaria officinalis): “Bruised and agitated with water, it raises a lather like soap, which washes greasy spots out of clothes. A decoction of it, applied externally, cures the itch.” It still washes things beautifully, and does soothe irritating skin conditions. It should not be taken internally since it has uncomfortable side effects. In Culpeper’s day it was used as a “cure for gonorrhoea”.

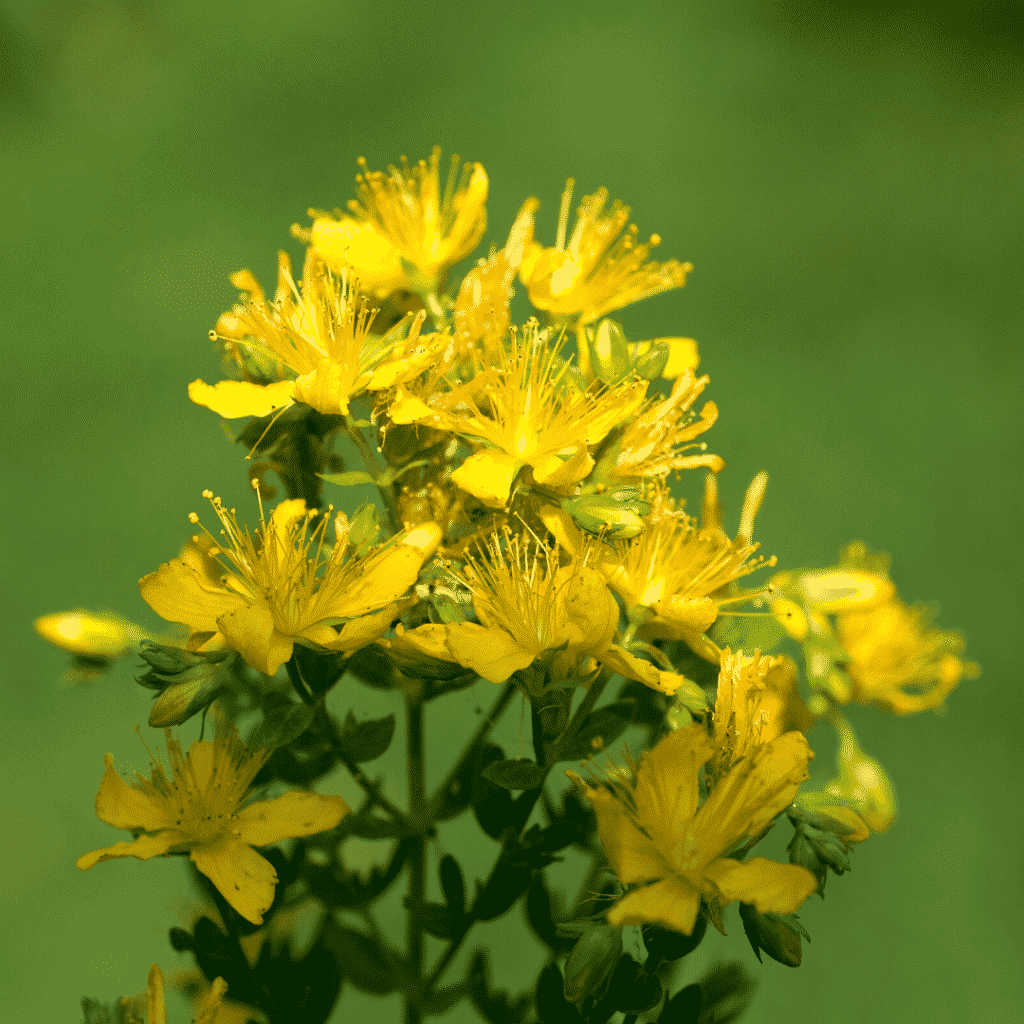

Probably one of the most famous worts today is our next candidate.

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): Listen to what Culpeper said: “A tincture of the flowers in spirit of wine, is commended against the melancholy and madness.” He could have written today’s ads! It was also used to destroy worms in the system, helped to “make water” and alleviate vomiting and spitting of blood, and as an ointment or poultice for closing wounds and dissolving swellings.

Did you know there is also a St. James’ wort? More commonly known as Ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) it was used for cleansing ulcers or mouth sores, quinsy, and eye, nose and lung seepage. A poultice, distillation or ointment was used for facial and “privacy” sores, sciatica and other skin or muscle problems. Today, we’re told that ragwort may irritate the liver if taken internally, but in external applications does just as it was once claimed: heals flesh ulcers and wounds and soothes inflammation of the eyes.

Goodness, we haven’t even touched on housewort, brownwort, crosswort, figwort, saltwort, moonwort – and a host of others. Maybe another time we’ll explore those worthies, but for now, there’s a lot of checking to do to see just how many worts our landscapes have!

Originally published in the Bonner County Daily Bee 3/18/01

Responses